We're here to talk about the rise of the API-focused application, and how it

interacts with templates for rendering HTML for web browsers. The simple point I hope

to make is: you don't necessarily need to use all client side templates in order

to write an effective API-centric web application.

I'll do this by illustrating a simple web application, with a single

API-oriented method (that is, returns

JSON-oriented data), where the way it's rendered and the style of template

in use is entirely a matter of declarative configuration. Rendering of

full pages as well as Ajax delivered "fragments" are covered using both

server- and client-side rendering approaches.

API Centric Development

Most dynamic web applications we write today have the requirement that they

provide APIs - that is, methods which return pure data for the consumption by

a wide variety of clients. The trend here is towards organizing web applications

from the start to act like APIs. In a nutshell, it means we are moving

away from mode of data models injected into templates:

def get_balance(request):

balance = BankBalance(

amount = Amount(10000, currency="euro"),

as_of_date = datetime.datetime(2012, 6, 14, 12, 0, 0)

)

return render_template("balance.html", balance=balance)

and instead towards returning JSON-compatible data structures, with

the "view" being decided somewhere else:

@view_config('balance', renderer='json')

def balance(request):

return {

'amount':10000,

'currency':'euro',

'as_of_date':'2012-06-14 14:12:00'

}

This is a fine trend, allowing us to make a clearer line between server side concepts

and rendering concepts, and giving us an API-centric view of our data from day one.

Templates

There's a misunderstanding circulating about API-centric development which says that we have to

use client side templates:

API-centric development. If you take a client-side rendering approach, odds

are the server side of your web application is going to look more like an API

than it would if you were doing entirely server-side rendering. And if/when

you have plans to release an API, you'd probably already be 90% of the way

there. (http://openmymind.net/2012/5/30/Client-Side-vs-Server-Side-Rendering/#comment-544974348)

and:

Lastly, another issue i can see, assuming you develop using MVC. You need

to have the view, model and controller very tightly coupled to make his

way work. The controller needs to know how the view works to create html

that can slot right in. It's easier if the controller only has to pass

data, not layout information.

(http://www.reddit.com/r/programming/comments/ufyf3/clientside_vs_serverside_rendering/c4v5vjb)

This second quote is specific to the approach of delivering rendered HTML

in an ajax response, to be directly rendered into a DOM element, which we will also demonstrate here.

How the "model" is more tightly coupled to anything when you have a

server side vs client side template, I have absolutely no idea.

Why might we want to stick with server side templates? As a Python

developer, in my view the main

reason is that they are still a lot easier to develop with,

assuming we aren't developing our server in Javascript as well.

Consider if our bank account balance needed locale-specific

number, currency and date formatting, and also needed to convert the timestamp

from UTC into a preferred timezone. A server side approach allows us to easily inject

more functionality into our template as part of its standard environment

for all render calls, such as something

like this:

def render_template(request, template, **template_ns):

number_formatter = number_formatter(request.user.preferred_locale)

template_ns['currency_format'] = currency_formatter(number_formatter)

template_ns['date_format'] = date_formatter(

request.user.preferred_timezone,

request.user.preferred_date_format)

return lookup.get_template(template).render(**template_ns)

The template can, if it needs to, call upon these methods like this:

<ul>

<li>Balance: ${data['amount'] | currency_format(data['currency'])}</li>

<li>As of: ${data['as_of_date'] | date_format}</li>

</ul>

With a client side template, we have to implement all of currency_formatter,

number_formatter, date_formatter in Javascript. These methods

may need to respond to business-specific inputs, such as specific user preferences

or other rules, that also need to be pushed up to the client. All the additional Javascript

logic we're pushing out to the client brings forth the need for it to be unit

tested, which so far means we need to add significant complexity to the testing

environment by running

a Javascript engine like node.js or something else in order to test all this

functionality. Remember, we're not already using node.js

to do the whole thing. If we were, then yes everything is different, but I wasn't planning on abandoning

Python for web development just yet.

Some folks might argue that elements like date conversion and number formatting should

still remain on the server, but just be applied by the API to the data

being returned directly. To me, this is specifically the worst thing you can

do - it basically means that the client side approach is forcing you to

move presentation-level concepts directly into your API's data format.

Almost immediately, you'll find yourself having to inject HTML entities for

currency symbols and other browser-specific markup into this data, at the very

least complicating your API with presentational concerns and in the worst case

pretty much ruining the purity of your API data. While the examples here may

be a little contrived, you can be sure that more intricate cases come up

in practice that present an ongoing stream of hard decisions between complicating/polluting

server-generated API data with presentation concepts versus building a much heavier client

than initially seemed necessary.

Also, what about performance? Don't client side/server side templates perform/scale/respond

worse/better? My position here is "if we're just starting out, then who knows, who cares".

If I've built an application

and I've observed that its responsiveness or scalability would benefit from some areas switching

to client side rendering, then that's an optimization that can be made later.

We've seen big sites like LinkedIn switch from server to client side rendering,

and Twitter switch from client to server side rendering,

both in the name of "performance"!

Who knows! Overall, I don't think the difference between pushing out json strings versus HTML fragments

is something that warrants concern up front, until the application is more fully

formed and specific issues can addressed as needed.

The Alternative

Implementing a larger client-side application than we might have originally

preferred is all doable of course, but given the additional steps of building

a bootstrap system for a pure client-side approach, reimplementing lots of

Python functionality, in some cases significant tasks such as timezone conversion,

into Javascript, and figuring out how to unit test it all, is a lot

of trouble for something that is pretty much effortless in a server side system -

must we go all client-side in order to be API centric?

Of course not!

The example I've produced illustrates a single, fake API method that produces a grid

of random integers:

@view_config(route_name='api_ajax', renderer='json')

def api(request):

return [

["%0.2d" % random.randint(1, 99) for col in xrange(10)]

for row in xrange(10)

]

and delivers it in four ways - two use server side rendering, two use client

side rendering. Only one client template and one server side template

is used, and there is only one API call, which internally knows nothing

whatsoever about how it is displayed. Basically, the design of our server component is un-impacted

by what style of rendering we use, save for different routing declarations

which we'll see later.

For client side rendering of this data, we'll use a handlebars.js

template:

<p>

API data -

{{#if is_page}}

Displayed via server-initiated, client-rendered page

{{/if}}

{{#unless is_page}}

Displayed via client-initiated, client-rendered page

{{/unless}}

</p>

<table>

{{#each data}}

<tr>

{{#each this}}

<td>{{this}}</td>

{{/each}}

</tr>

{{/each}}

</table>

and for server side rendering, we'll use a Mako template:

<%inherit file="layout.mako"/>

${display_api(True)}

<%def name="display_api(inline=False)">

<p>

API data -

% if inline:

Displayed inline within a server-rendered page

% else:

Displayed via server-rendered ajax call

% endif

</p>

<table>

% for row in data:

<tr>

% for col in row:

<td>${col}</td>

% endfor

</tr>

% endfor

</table>

</%def>

The Mako template is using a <%def> to provide indirection between the rendering

of the full page, and the rendering of the API data. This is not a requirement,

but is here because we'll be illustrating also

how to dual purpose a single Mako template such that part of it can be used for a traditional

full page render as well as for an ajax-delivered HTML fragment, with no duplication. It's

essentially a Pyramid port of the same technique I illustrated with Pylons four years ago

in my post Ajax the Mako Way, which appears to

be somewhat forgotten. Among other things, Pyramid's Mako renderer does not appear integrate

the capability to call upon page defs directly, even though

I had successfully lobbied to get the critical render_def() into its predecessor

Pylons. Here, I've implemented my own Mako renderer for Pyramid.

Key here is that we are separating the concept

of how the API interface is constructed, versus what the server actually produces.

Above, note we're using the Pyramid "json" renderer for our API data.

Note the term "renderer". Interpreting our API method as a JSON API,

as a call to a specific client-side template plus JSON API, or as a server

side render or ajax call is just a matter of declaration. The way we

organize our application in an API-centric fashion has nothing to do

with where the rendering takes place. To illustrate four different ways

of interpreting the same API method, we just need to add four different

@view_config directives:

@view_config(route_name='server_navigate', renderer='home.mako')

@view_config(route_name='server_ajax', renderer='home|display_api.mako')

@view_config(route_name='client_navigate', renderer='display_api.handlebars')

@view_config(route_name='api_ajax', renderer='json')

def api(request):

return [

["%0.2d" % random.randint(1, 99) for col in xrange(10)]

for row in xrange(10)

]

The rendering methods here are as follows:

- Method One, Server Via Server - The api() view method returns the data, which

is received by the home.mako template, which renders the full page,

and passes the data to the display_api() def within the same

phase for all-at-once server side rendering.

- Method Two, Server Via Client - A hyperlink on the page initiates

an ajax call to the server's server_ajax route, which invokes the

api() view method, and returns the data directly to the display_api

def present in the home.mako template. For this case, I had to

create my own Pyramid Mako renderer that receives a custom syntax,

where the page name and def name are separated by a pipe character.

- Method Three, Client Via Server - Intrinsic to any client side rendered

approach is that the server needs to first deliver some kind of HTML layout,

as nothing more than a launching point for all the requisite javascript

needed to start rendering the page for real. This method illustrates that,

by delivering the handlebars_base.mako template which serves as the

bootstrap point for any server-initiated page call that renders with

a client side template. In this mode, it also embeds the data

returned by api() within the <script> tags at the top of the page,

and then invokes the Javascript application to render the

display_api.handlebars template, providing it with the embedded data.

Another approach here might be to deliver the template in one call, and

to have the client invoke the api() method as a separate ajax call,

though this takes two requests instead of one and also implies adding

another server-side view method.

- Method Four, Client Via Client - A hyperlink on the page illustrates

how a client-rendered application can navigate to a certain view,

calling upon the server only for raw data (and possibly the client

side template itself, until its cached in a client-side collection).

The link includes

additional attributes which allow the javascript application to call

upon the display_api.handlebars template directly, and renders it

along with the data returned by calling the api() view method

with the json renderer.

Credit goes to Chris Rossi for coming up with the original client-side

rendering techniques that I've adapted here.

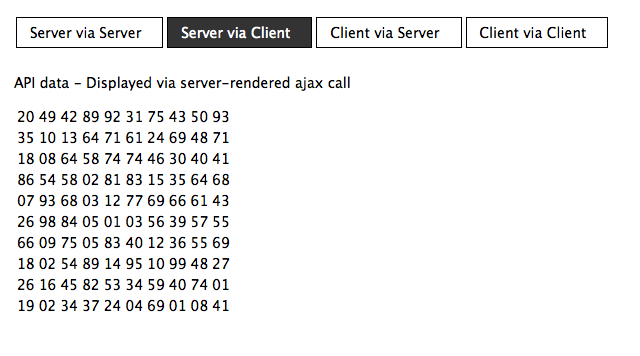

A screen shot of what we're looking at is as follows:

The demonstration here is hopefully useful not just to illustrate the server

techniques I'm talking about, but also as a way to play around with client

side rendering as well, including mixing and matching both server and client

side rendering together. The hybrid approach is where I predict most

applications will be headed.

You can pull out the demo using git at https://bitbucket.org/zzzeek/client_template_demo.

Enjoy !